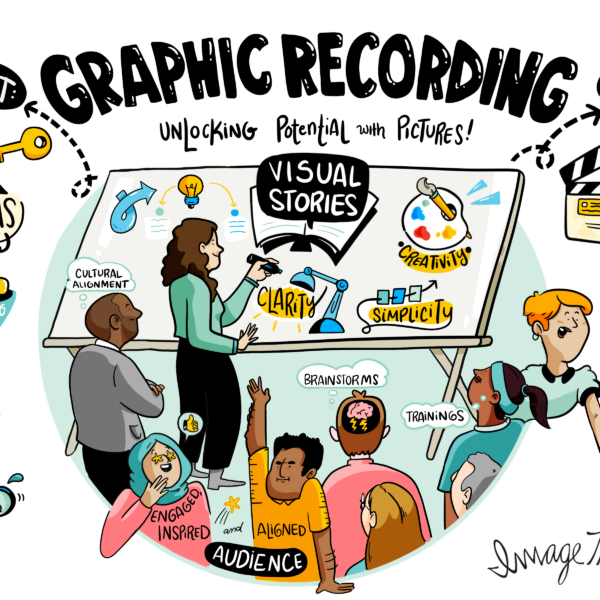

Introducing Dan Seewald: The Innovation Expert

Nora Herting: Hi, welcome everyone to the eighth installment of Image Think series, Ask the Expert, where I sit down remotely with leaders and innovators to get to explore the more practical application of all their expertise and our everyday business setting. These events are also your opportunity to ask our experts anything you’d like. Type out any questions you have in the chat on LinkedIn, or for those of us joining us from Clubhouse, welcome, raise your hand or post your comments in Clubhouse as well, and we’ll address them.

Nora Herting: For all of you who don’t know, I’m Nora Herding, the Founder and CEO of Image Think, a visual facilitator, a graphic recorder, thinker, and author. A few weeks ago, I received a newsletter email from Dan Seewald. I was so excited about the article, I immediately emailed him and asked if he would be our next guest expert.

Nora Herting: Fortunately, Dan said yes, and I’m excited to bring to you the experience, the insightful approach and the wealth of knowledge that Dan brings to the topic of innovation. Actually, this month, instead of Ask the Expert, we’ve renamed it in honor of Dan and called it Ask the Innovator. Dan, thank you so much for joining us. Really excited about this conversation.

Dan Seewald: Thanks for having me. What an honor to be the inspiration for a new brand name. It’s not often that people tell me that.

Dan Seewald’s Background

Nora Herting: We like to change it up. Before we get started, I want to try to distill your amazing credentials and bio for the audience here. For those of you who don’t know Dan Seewald, he is a professor, a facilitator, a moderator, and a featured TED Talk keynote speaker.

Nora Herting: Dan advises and applies the deliberate innovation system, which is a methodology used to transform the traditional innovation workshop and advisory board experience by blending behavioral science with design thinking, and it’s brilliant. Dan is also the former head of Pfizer’s Worldwide Innovation Group, where he architected and led the DARE to Try program, which was one of the Fortune 100 companies leading corporate innovation programs. It’s really impressive to think about such an innovative company like Pfizer and Dan, setting up the entire program and training innovators across the entire enterprise.

Nora Herting: Now, clients seek out Dan because he has a foot both in the corporate world as well as a number of companies that are startups. He’s also a certified coach. What I say coach, I don’t just mean the mental coach that we’re thinking about, but Dan is also an actual wrestling coach, so he really lives what he does.

Leveraging Metaphor in Innovation

Nora Herting: Again, thank you so much, Dan, for joining. I know we have so much to cover today, but I wanted to start with the article that I mentioned that made me so excited for you to be a guest on our show, and that is using metaphor.

Nora Herting: We talk about metaphor at ImageThink. We use it a lot at ImageThink to help communicate, for leaders to communicate the direction of strategy or to create a story of change. But what was so compelling about your piece is you’re advocating for using metaphor way before decisions are made, but really as a vehicle for problem-solving innovation. I’m going to stop there and turn it over to you, and maybe you can tell us a little bit about deodorant and metaphor.

The History of Metaphors

Dan Seewald: Yeah, I’m glad you bring it up about metaphors because it is not my own inspiration. The idea of metaphors as a source of new or more novel ideas has been around for nearly 100 years.

Dan Seewald: What’s old is new. It’s Ecclesiastes. We learned from the past, but it goes back to a method called TRIS, which a Russian cosmonaut who was in prison in a gulag had worked on while he was in prison. It’s been evolved in multiple other incarnations; a guy named Bill Duggan from Columbia University.

Dan Seewald: It’s far from new, but what I find is most organizations, most innovators do not tap into the power of metaphors.

Dan Seewald: Metaphors, what makes them so important and so powerful, it allows us to think, where else has your problem or your need been seen before, and where has it been solved? That simple question opens up a myriad of possibilities. You could look at a business challenge and look far afield to agriculture, to metaphysics, to robotics, to other companies like Netflix or Airbnb. It starts to invite many different inspirations by thinking, where else has this been applied? How did it work there? How can I apply it in my own world? That’s what’s powerful is that we sometimes get trapped in our own world, our own business, our own brand and teams. Because of that, we get this myopia. This use of metaphors allows you to look far outside.

Practical Application of Metaphor in Innovation

Dan Seewald: Thinking of deodorant, that you brought that up. That’s a really old story that also when dusted off, people love to hear about it because long ago, there was a deodorant company that back in the old days, it had a spray deodorant.

Dan Seewald: That’s how they would apply it. They found when they sprayed it in their armpits, it got all over the place. It got on their shirts, it got on their shoulders. It was very inconvenient. People were not clamoring, I want something brand new, but they’d complained about it. The company started to think about how could we solve this? They went through all the normal trials and tribulations of doing product development. They just didn’t come up with anything novel or they felt that really solved the problem. One guy who’d been exposed to Tris had said, “Well, where else do we have trouble consistently applying a spray or a fluid?” They started to look at a lot of places, painting, painting a house.

Looking Elsewhere

Dan Seewald: They started to look in other places as well. They looked in lawn care and then they spotted something really interesting, the ballpoint pen.

Dan Seewald: For those who maybe remember the old days of using a fountain pen, I remember my grandfather teaching me calligraphy with the fountain pen, you’d get ink all over your hands and it would spread everywhere. I was a terrible calligrapher.

Dan Seewald: But what it really taught them or showed them is that the ballpoint allowed you not to spread ink everywhere, it kept it very isolated, and it used a rollerball technology. So, they said, “Aha, this is the big idea or the inspiration for insight, if you will.” And they said, “Well, what if we applied the rollerball technology to deodorant?” Which they did and it ultimately became the Ban Roll-On, if you know the company Ban.

Borrowing Inspiration

Dan Seewald: The Ban Roll-On was inspired by the roll ball technology in a ballpoint pen. So, they borrowed inspiration and metaphor from a completely disparate field, something they probably wouldn’t have looked at. They wouldn’t have gone to a writing company or an ink company like Bic or any other companies that were developing the rollerball. They would have gone to the usual suspects. But by doing that, they found inspiration allowed them to think about the problem and a solution in a completely different way.

Dan Seewald: And if you look throughout product development, more times than not, people talk about being serendipity, but it’s not serendipity. It’s seeing things in other places that may not have applied immediately, but they’ve found a metaphorical relationship. So, I believe that you can actually harness this type of inspiration yourself. In fact, I know you can. And it takes a little bit of work. It doesn’t happen the first time. The more the metaphors, the merrier and the better. So that’s a little bit about metaphors. There’s lots of great ones out there. You’ll see them yourself. Happy to share more of them. But that’s a little bit about metaphors and why I feel so passionate about it. I see them create breakthroughs all the time. So that’s why we started to kind of lean into this with deliberate innovation.

How to Apply Metaphor to Problem-Solve

Nora Herting: Yeah, I love that story. It’s a great story too, because it also underscores, it doesn’t have to be a completely original idea, right? As you said, the roller ball technology already existed. It was just that it was in a different industry, and it wasn’t applied to deodorant. And so, it was an innovation within that industry. And I think oftentimes I see lots of clients just look within their own industry to their competitor.

Nora Herting: This is a great reminder of it. For those of us that would like to try this out, for folks on LinkedIn, which is great. I’m seeing there’s folks from the UK, from the Czech Republic, from New York, and those on Clubhouse, what would you say might be one or two tips for, if they want to try to put this practice of metaphor to help innovation or breakthrough problem solving that they should start with, Dan?

Start Simple

Dan Seewald: Yeah, I think the easiest thing to do is take a simple problem that you’re facing. Could be in your personal life. It could be in your professional life. Write it out as a clear problem statement. And while our goal is not to talk about problem definition, which I really do believe is that if you understand the problem first and really deep understanding, you’re going to be in a much better place to use metaphors.

Dan Seewald: Try to write it as a question, a how might we question? So how might we find more time to enjoy our children? How might we be able to get our laundry to wash itself? Cause we don’t have enough time for our laundry to get washed cause we’re so busy with our children. Take a mundane challenge or take a more, slightly complex challenge that you have in your workplace. State is a question and then start by asking, where else has somebody seen a problem like this before?

Generalize Your Problem

Dan Seewald: Now it may take you a little bit of work to unpack your question. Cause a lot of times the questions are so convoluted and filled with business speak, we lose the intent of what the actual problem is. You think about the big example, or the Ban Roll-on example, they looked at it and said, we’re having trouble applying a deodorant, but what they’re really facing is it applied unevenly. So where else do you see things that apply unevenly?

Dan Seewald: Take your problem, try to agnostically translate it, or in other words, generalize it in such a way that you might have to keep peeling it back a little bit more and a little bit more. Tell it to a child or to somebody who knows nothing about the problem. Once they sort of understand the essence of it, then you can ask them, where else have you seen something like this?

Practice Innovation

Dan Seewald: You’ll be amazed how quickly people say, oh yeah, that’s kind of like this, or it’s kind of like that. Some of them may be very obvious ones and that’s okay. But the more you dig, the more you practice, doing it yourself or asking a few friends, you’ll start to find more and more interesting metaphors that can unlock the potential. So start with something real in your life and then go from there.

Dan Seewald: And it is like anything else in life, it’s about habit. You got to practice it. A lot of people will say to me, ah, this doesn’t work, I tried it. How many times did you try it before? Once, twice, that’s not enough. And you mentioned about coaching, there is no way anybody would ever step foot on a mat to wrestle or step foot on a soccer pitch to play soccer without having practiced over and over and over again. So, it’s about habit and practice and working on it. So, if you don’t get the first time, it doesn’t mean it doesn’t work. It just means you got to work at it. So that’ll be a little bit of my suggestions about what you can do individually.

The Problems We Face Aren’t Unique

Nora Herting: Great, that’s so helpful. So, it sounds like if we went into just fill that down, one is choose a real problem that you have. And I’d love to hear from some folks that maybe want to throw out some that they might have on LinkedIn in the comment section. Today, if you make a comment, we’re going to choose somebody who’s posted a comment or question to receive a copy of our book, Draw Your Big Idea. So I’d love to hear from folks. What is that problem? Make it real. And then it sounds like you’re also saying, distill it down. I love what you’re saying. Imagine that you’re talking about what is the root problem when you strip everything else away. And I think that’s great because then it should be easy to see how it must relate to someone else.

Nora Herting: I think a lot of times when we, if we don’t do that, we think, “Oh, our problem is so specific to our industry. Oh, our problem is so specific to our division, our clients,” right? And one thing I’ve noticed in 12 years of doing the work at ImageThink, and when people say, well, how can you support a pharmaceutical meeting? Or how can you support a meeting at NASA without obviously a science background? It’s because really the truth is, once you bake it down and you boil it down, most organizations are really wrestling with the same few problems. Does that sound, as someone with a background at Pfizer – would you in your work agree with that, Dan?

Similarities in Problems Across Industries

Dan Seewald: It definitely resonates. Yeah, I would say I’ll double down on that comment because the work that I’ve done in healthcare, life sciences, pharmaceuticals for a couple of decades, you would say, “Wow, you’re really a vocational expert just in healthcare. How could you possibly help out an oil and gas company?” Or “How could you possibly understand industrial manufacturing?” And there are a couple of things I would say, or a few things I would say about that. Number one is that the practices of applied creativity innovation cut across industry. The second thing is highly regulated industries and companies are more alike than they are dissimilar.

Dan Seewald: You find these very similar patterns across them. And I hear the same statements, the same concerns, the same obstacles. And that doesn’t eliminate the uniqueness that a chemical manufacturer faces versus a company that does architectural glass, for example. They are different, but there’s also a lot of verisimilitude. So, you find those, and you see how you can search for solutions across that matrix.

Dan Seewald: And in fact, that’s one of the great things about working across a lot of industries. What works in glass manufacturing may also work in biotech, but they don’t see each other. They don’t talk to each other. So, one of the other things that we do a lot of is that we will run panels and events where we bring in external thinkers from other industries, other disciplines to join our colleagues, our clients, so that they will bring a different perspective. But that means that we have to understand it. We need to really dig in, listen and ask great questions so that we can get to the essence.

Getting Simplicity from Nuance

Dan Seewald: And while the simpler seems like it’s not important to have, it’s better to have the nuance, it’s getting from the nuance and getting to the simplicity, which is what matters. That’s what allows you to get to the metaphors. It’s what allows you to find and source people from different domains to solve your problem. So, I really do think that the more dissimilar we think we are, you’ll be amazed to see how much more alike you are than you think.

Nora Herting: Yeah, that’s great. I love that. A move from the nuance to the simplicity because I completely agree. And that I think is something, a gift that you and I at arbor can bring to clients is being able to have that privilege of working across industries and seeing that we’re not so special with the things that hold us back or challenges we have. I’m sure there’s lots of people who are joining us right now that have some of the same topics or problems that they think are so special or maybe just they’re dealing with in their own industry that are across industries.

Nora Herting: Something else that came up that I’d love to have you touch upon in the story about metaphor is one limitation I think is we stay in our own jar dinner, our own industry and we don’t look across them. But another one is something called the expert’s dilemma. So do you want to speak maybe a little bit about what that is and how people can try to break out of the expert’s dilemma.

The Expert’s Dilemma

Dan Seewald: Yeah, so there’s a couple of ways to think about this. So the expert’s dilemma or sometimes I refer to as the knower’s mindset. It harkens back to the work about the fixed mindset – Carol Dweck for a book somewhere in the back of my shelf here. Carol Dweck was worked in academia and education, and she talked about the fixed mindset versus the growth mindset. Well, when it comes to innovation and organizations, there is a slight kind of nuance or a different play on that which is the expert’s mindset, which can be often falsely evenly equated to the fixed mindset. And then there’s the learner’s mindset.

Dan Seewald: So let me step back for a second and just tell you a couple of things about the expert’s mindset. When you are in a highly regulated company like a pharmaceutical or in an oil and gas company or a bank, you rely on people to be experts. You need for the experts to be there. So, it’s not a bad thing to have expertise.

The Common Critique of Experts

Dan Seewald: In recent times, we’ve heard a lot of critique of the experts. Oh, the experts think they know, they get it wrong. And there was actually some research a guy named Philip Tetlock from the University of Pennsylvania. He did very longitudinal research about forecasting and expertise and that often the experts don’t know and not get it right, but it could be most not so different than a coin flip when it comes to forecasting which begs the question, do the experts know?

Dan Seewald: Well, they do, they need some shaping of their thinking, and we rely on them because we don’t always have the deep expertise, but the challenge is that you get so wedded to your supposition, so wedded to your beliefs that it can be very difficult for you to think outside of the known and the familiar. And that’s why it’s really important. We not just have our experts and subject matter folks that are involved in things but that we coach our experts to be able to stop and challenge their thinking. It’s really hard.

Dan Seewald: If you’ve done a PhD and you’ve done a postdoc and you’ve spent years in a very focused area and somebody says, you know what? You should question the basic assumptions of what you do. You probably say, I don’t believe this malarkey. Like I’m going to look at this the way I’ve always looked at it, why should I challenge the way I’ve done things? It’s worked for me. It got me where I am. And the challenge is that as an expert and a company that relies purely on expertise is that you’re going to do things the way you’ve always done them before.

Challenging Basic Assumptions

Dan Seewald: So, you have to be able to challenge your basic assumptions and it’s not so easy. People talk about it but there’s technique and method to be able to get the experts to be able to not just be knowers but also to be learners. And it’s tricky, it’s very, very tricky.

Dan Seewald: And one more thing I’ll say, it’s not just the subject matter experts or opinion leaders in an organization or an institution. It’s also the senior leaders because what got them where they are, has been their expertise, their insider knowledge. So, to do things different is very tricky but if you don’t do things differently, you’re going to end up in sort of this endless cycle of corporate ennui, just the things being the way they always were. And we know disruptors are out there we need to eat your lunch. So, they have to think different, but they’ve always have done it that way. And that is the dilemma that you face as an expert or as an insider in any institution or industry.

Embracing the Learner’s Mindset

Dan Seewald: So, you have to embrace a learner’s mindset. You have to practice it all the time because otherwise you’re just going to fall into the known and familiar patterns that you’ve relied on your whole career and most people have applauded. So, I would say that this only touches the surface of it. It sounds easy, it’s not, it’s very difficult and it’s even more difficult to get any organization to start to challenge their experts because they need them, and they don’t want to ruffle their feathers.

Nora Herting: Right.

Dan Seewald: So, it is difficult, very difficult situation.

Nora Herting: It is really difficult. And those of you, I see some questions coming and this is a great time to pause for those. If you have a problem you’re stuck in, this is a chance to run it by Dan.

Nora Herting: Also talking about unpacking the expert’s dilemma which I do see as a really big limitation of whenever we have success, right? So, Eric is thinking about that as well. And so, his question for you, Dan is how do you address organizations which have a key need of innovation? Yet the experts are risk averse, they play it safe. They have personalities that play it safe. And they basically are posing barriers to that innovation. So, I think this is Eric is in kind of the world of the expert’s dilemma.

Nora Herting: You acknowledge that it’s really hard because it’s the thing that has made you successful. And maybe at that point, there’s not enough pain to have to change or to look at it differently. So, Dan, what would you recommend for Eric here?

Challenging Expertise

Dan Seewald: So, there’s a lot of ways that you can go with this, and it depends on your you’re talking to the organization, do they have the control and influence to make a change? Are they kind of in the trenches and then you take a slightly different approach based on where they are in the matrix, the hierarchy of the organization. But let me take somebody who has more control than just indirect influence, a senior leader, which there’s plenty of experts who are kind of in that mode.

Dan Seewald: The question to ask them is, is what do you see happening in the next couple of years? What changes are afoot? And do you think it’s going to impact you? And a lot of times we’ll give them examples and try to avoid the trite examples of Kodak. Look what happened with Kodak when they missed the opportunity when it came to digital photography. We look for ones that are maybe adjacent or directly related to their industry so they can see what happens when you follow a safe and steady path. And there’s lots and lots of examples of this, but you wanna be able to tie it back to the behaviors that leaders embraced or didn’t embrace for that matter. So it’s literally showing or shining a light on them and showing where they are today, but where they could end up being.

The Uber Innovation Example

Dan Seewald: Classic example that I’ll share. A gentleman who will remain unnamed, he was the owner of a black car company. We spoke many years ago when I first moved into my neighborhood, one of the largest kinds of car services in the Northern New Jersey area. Very big business – took it over from his family. And this was at the time that Uber was just kind of becoming a name, but a lot of people didn’t know it. They didn’t think it would make a big difference. And I asked them, what do you think about Uber? How’s it going to affect the black car service business? And he said, this isn’t going to make a difference. It’s just in loyalty.

Dan Seewald: We’re not going to do anything different. What got us here is what’s going to keep us here. And it was very insistent and very dismissive. And as I kind of pressed about Uber, he said that nobody’s going to Uber my business. Well, fast forward a few years later, probably about three, four years later, I ran into him again. And we were just chatting. He clearly had no memory of our conversation we had at this barbecue.

Fallout from Industry Disruption

Dan Seewald: I said, “Hey, how’s business going?” And he said, “We’re getting killed. We’re down 30%. A lot of our customers that we were used to having who relied on us, they’re starting to jump ship and go into these ride share services. And we’re just trying to figure out how to keep up.” And he is kind of a telltale story that he could have done something earlier on.

Dan Seewald: What I don’t know, but certainly there are things he could have done. He could have increased loyalty. He could have built in something else into his business model. Could have diversified his portfolio. A lot of things he could have potentially done, but because he was unwilling to stare the alternative in the eyes, then he faced it. He faced the consequences, that is. So for me, when you talk to a leader, maybe even somebody who is the rank and file, who’s an expert, who’s very resistant, give them examples about what some of the alternatives are. And they don’t have to be these huge mega examples like Blockbuster and how they got disrupted by Netflix or Airbnb and Hilton and other companies like that. They could be very mundane examples.

There’s Always a Disruptor

Dan Seewald: I find that when I bring those up, it gets people to stop and think and pause and say, what am I doing differently? And that could be actually losing your tenure, your role in an organization. It could be being disrupted directly by a competitor, but it could also be a bigger story or just a mundane one like this guy in his black car service. So, people need to hear, they need to know that you’re never safe. There’s always a disruption right around the corner. And actually, one last thing I’ll say is that you think about a recession-proof industry. One of the ones that comes to my mind is haircutting, hair stylist. There’s always a need for hair stylist, right?

Dan Seewald: People are for the most part are growing hair, hopefully. And there’s a demand for it. And if you were owned a salon and you for years have been running that salon, you’re probably thinking, I’m just going to keep doing what I’ve done. Well, just about a week or two ago, Amazon announced that in the UK, they’re launching one of their beta tests to see how they can use augmented reality and AR in opening up salons.

Looking for Low Hanging Fruit

Dan Seewald: So, you might think that you’re untouched, but they’re out there. The disruptors are waiting and there’s tons of startups. We work and collaborate with lots of them. They’re always thinking about, where’s the low hanging fruit? How can I get into your industry? So, if you’re an expert, you’re an incumbent and you feel like, hey, it’s worked, don’t mess with it. Look around, you’re going to see lots and lots of bodies piled up, so to speak, of people who said the exact same thing.

Nora Herting: So, it sounds like, all of that’s true and it’s usually very chilling. The Blockbuster story is its own sort of metaphor now, about needing to innovate, but it sounds like Eric, your advising needs to have some kind of tough love conversations and maybe a little bit of fear and urgency with those folks. But certainly Eric, you’re not alone in what you’re encountering.

Innovation Requires a Shift in Mindset

Nora Herting: I think that it’s a hard mindset, even if you’re the expert, you’re trying to shift that mindset. So great questions, keep posting them. We have another one. For you too. Kelly Ford is actually Director of Global Patient Strategy and Engagement and Inflammation and Immunology at Pfizer.

Nora Herting: And Kelly’s question is, how do – oh, she’s got, there’s two questions here. Oh, sorry, this one’s from Kelly Evans, Director of Digital Strategy Design at Salesforce. So, we’ll come back to the other Kelly. Great questions are, this one I think you’re really going to love to answer is, how do you get beyond innovation theater to real innovation?

Dan Seewald: Yeah, actually I’m going to sort of piggyback on that. Cause the last thing I was gonna say is for Eric, you know, Eric, you can scare people. Fear is only a short-term motivator for change. We found that through change management. It might be the thing that jars them and pushes them and says, “Hey, you’ve got to do something.” But the next thing you need to do is you got to go from that to actually the real doing. And that’s around giving them example, giving proof and giving method and practice to do things differently. So that’s very close to Kelly’s question, Kelly Evans’s question, which is how do you go beyond innovation theater?

Going Beyond Innovation Theater

Dan Seewald: Innovation theater, for those who it’s become almost like a jargony term, but it’s a real thing. It’s all pomp and circumstance and show, you get everybody jumping around and you introduce a couple of fun things about creativity and people have a good experience, which by the way, it does matter. But then there’s no stake behind the sizzle, so to speak. So, you actually have to give people real things to do. You need to work on real problems. You need to teach and inculcate these practices within people. If you don’t do that, then it is all theater. So, what I find is you have to have a healthy balance between a little bit of theater because there are going to be people you have, and it should be fun, but it should also be meaningful. So, you have to have that balance.

Dan Seewald: And until people do it themselves, till you get their kind of hands dirty, it’s all theoretical. It’s all, it is still kind of theatrical or show. So, get people’s hands dirty, give them some relatable tools, get them to practice it. And I may talk about this later, but I’ll just say it now. The best way to really learn something is to play it as a game. So, learn it as a game, practice it. And then once you’ve kind of done that in a risk-free environment, then you’re ready to let them do it for real. And that’s where you move beyond the theater, and you get into the realm of the real.

The Truth About Innovation: It’s Messy!

Dan Seewald: And I’ll say this now, that innovation is dirty. It’s hard, it’s messy. Any person who’s run a startup company or launched a new venture will know that the excitement of that first burst of insights and ideas, that will keep you warm at night. That’s the thing that’s going to keep you going. But then you got to roll up your sleeves.

Dan Seewald: You got to get in there and you have to do work, you have to talk with customers, you have to iterate. You have to accept that things are not going to work out the way you thought they were. People who think a polished idea is going to come right out of a workshop and “Voila!” I have what I need, you’re buying it to theater. And you’re just as guilty as the people putting on their performance. So, accept that it’s going to be hard. It’s going to be messy, but anything worth doing is worth putting the effort and getting the sweat on your brow for. So, it’s important to have a little bit of sizzle, but you got to give them some stake also.

Ideas are a Commodity

Nora Herting: I think that that’s great. You got a lot of passion there. I love the steak to me and tell me what you think. In my experience is really about, and you have a great phrase, and I’ll get to it, I think that this is sort of what you’re talking about, is really about one, yeah, are they innovating about something that’s real? Is it a real problem? And the two, it really comes down to execution and leadership. Are there stakeholders, are there senior leaders that are endorsing this? And once the excitement of the workshop is over, is there a clear plan? Are people going to have the tenacity and the focus to move that from an idea to an action?

Nora Herting: Because it’s one thing to have a great experience. And I do think it’s important because for us in our own model, you need the engagement after you get the idea to move to the execution. So you need the buy-in, you need the excitement. But to me, the difference between just innovation theater and real change is what happens after the workshop, right? So I don’t know, Dan, would you say when you have this, I love this, which is this quote about ideas being commodities. Like an idea is a commodity.

Nora Herting: And my understanding that’s a little bit about, ideas are cheap, and execution is what’s going to really make the Ubers of the world or the innovators of the world conversation worthy.

Why Execution of Ideas is the Premium

Dan Seewald: A hundred percent. That’s ideas are commodities. Execution is the premium. And I think one of my professors, when I was years ago at New York University taking entrepreneurship class, he said, yeah, everybody’s got ideas. He had a much more crass way of putting it, which you might guess what that expression is. But the thing is that you have lots of ideas. The thing is you have to decide which one actually has potential, and which one are people going to have passion around, which is most relevant to solving, which ones are going to push the and break the rules or the conventions, if you will, around what you’re already doing.

Dan Seewald: That’s hard because you have to make choices. You can’t develop five concepts simultaneously. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve worked with teams and leaders that say, there’s 15 great ideas. I want to develop them all. Good luck. You know what’s going to happen? You’re going to do nothing. And that’s why you have to make choices.

Ideation

Dan Seewald: And you could do it serially. You can run experiments. Something fails, shunted to the side, and start a new one. It’s hard. People don’t like to admit failure or mistake. And it’s hard to actually turn back and say, let’s go back to the beginning. Everybody hates doing that. Most people hate doing that. But you have to make it a discipline. But once you accept the fact that ideas are commodities, it’s OK. It’s OK for things not to be perfect. And it’s OK for you to have ideas that are sprouting. They’re never going to actually see the light of day. But you have to really put your time in doing the development of those concepts. And that’s, as I was saying before, that’s where the hard work happens.

Dan Seewald: And just some sort of frame of reference is that a couple of years ago, other than doing advisory work and consulting with a lot of large companies, I put my money where my mouth is. And myself and a physician started a health care device company with a women’s FemTech product. It started with an awesome insight and an idea, which we were both really excited about. That’s the fun part.

Dan Seewald: Now it’s been two years or so of hard work, of iterating, prototyping, testing with people, learning why it’s not working, going back and actually saying, that didn’t work. Let’s go back to the drawing board, talking to customers all throughout the process and saying, “Yeah, that’s not working.” We’ve got to do this, all the while putting our capital and investors capital into it and saying, we don’t want to fail because you could talk about failure, but it’s hard to fail with other people’s money and it’s even harder with your own.

The Beginning of the Creative Process

Dan Seewald: So, the truth of the matter is that’s where the hard work comes is with any new venture or startup that you’re doing is that the idea is the starting point. You got to make the right choices, but then you got to put the time in. And there’s lots and lots we could talk about, where do you put the time and how do you do it? But that’s the beginning, if you will, for me of the creative process. It’s certainly not the end.

Nora Herting: So true, so true. So hopefully those are helpful, Kelly Evans, around how do you break it out of innovation theater. And it sounds like the answer is a little tough. One is we gave, Dan had some great tips about metaphor and simplifying the problem, but the other is, if you feel like it’s going nowhere, think about what is happening after the innovation session or that theater is over and what’s stopping it into coming to a full idea.

Nora Herting: So, all of you, some great questions. This again is your chance to ask Dan, the innovation expert, some questions about innovation problems that you’re having, post them in LinkedIn in the comment section. Thank you for those of you joining us on Clubhouse.

Empowering Patients to Lead Conversations with HCPs

Nora Herting: I want to come back to Kelly Ford, who has, I think her question is really, you know, maybe a question that she’s trying to innovate around. So perhaps you can help her rather come up with the solution, give her some tips for how she might look at it is she’s struggling with how to empower patients to lead conversations with the HCP so that they get what they want. I think that this comes up over and over again with all of our healthcare clients and empowering patients. So this might be – I see you nodding your head, Dan – a familiar question or challenge. What would be some ways that you might encourage Kelly, what would be a metaphor or a way that she could take this back and maybe have a breakthrough or have a more innovative conversation about how to tackle this?

Dan Seewald: So, it just so happens Kelly and I go way back. So, Kelly is someone who is a friend also and this is a question which I think most life science companies are grappling with of, you know, and there’s a lot of questions are grappling with but kind of empowered patient. So, over the past, oh, I would say maybe decade as we kind of march in technology becomes more proliferate and the shift of power starts moving towards the quantified and empowered patient that we look at how do they kind of change the balance of the dialogue in the past.

Framing the Problem

Dan Seewald: Patients were uncomfortable having a conversation with a physician. They may be uncomfortable asking them to prescribe a particular medicine or to consider something. And it’s very tricky because they are the expert, the physician, the HCP, that is, is the expert. And we don’t want to disturb the delicate genius. We don’t want to upset the person who is knowledgeable and trained in this. And sometimes, you know, if you think about the life of a physician, whether you’re in the United Kingdom or in the United States or most places in the world, physicians are really, really busy.

Dan Seewald: A friend of mine who is a physician said, on an average day, I’m seeing 40 patients during my office hours. That’s an incredible churn. So, you’re going to stop them and break their rhythm? It feels a little bit off-putting and uncomfortable. So, I think the question you’d have to do is unpack what’s stopping or getting in the way of that patient having the conversation.

Where Else Have We Seen This Problem?

Dan Seewald: One of the things I’ve articulated is it may be that they’re uncomfortable challenging the experts. So where else have somebody been uncomfortable challenging an expert? Where else has somebody felt like they didn’t have power, but they actually have been in a position where they needed to challenge experts? One place certainly that comes to my mind just off the top of the head is in the military structure. In the US military structure, for example, it would be almost unthinkable or it was unthinkable if you had a PFC, a private first class, saying to a captain, hey, I don’t think we’re doing things the right way, or maybe we should try this differently.

Dan Seewald: And that, I mean, that would be like grounds of insubordination, but there’s an analogy or a metaphor where it does work. In the Israeli military, it’s not unusual for a lower ranked officer or not an officer to challenge or ask questions of an officer. And you might say, well, that’s just cause they’re Israelis. That’s kind of culture. You can’t quantify culture, but actually I think it comes back to practice habit and things that they do. They actually allow them and power them to do problem solving.

Generating Metaphors

Dan Seewald: So, does that help solve Kelly’s question? I don’t know yet. We probably have to generate another half dozen or more metaphors and say, well, where else? What are some other ways that people felt where there’s an imbalance of power, one’s an expert, one’s not to advocate their point of view? And you’ll start to see some of these potential insights, these sparks, these proto insights, they’ll start kind of sprouting and those will give you the hunches that you need to be able to create a breakthrough. And I’m sure if we actually spent like another 15, 20 minutes and did enough thoughtful methodological way, we probably would get a dozen or more with this group, probably a lot more of these starter thoughts that could help Kelly solve that problem. So without solving the problem – that’s a bit for Kelly.

Nora Herting: For those of you listening and joining Ed, what would be to Dan’s challenge a metaphor, one would be a power imbalance. I was thinking also politically, possibly. Another potential problem is there’s time constraints, right? So, it would be a metaphor where you’re trying to have a conversation, you’re trying to get something done. There’s some time constraints. And I’ll certainly, when I see the doctor.

An Innovative Approach to Problem-Solving

Dan Seewald: I’ll just note something here, Nora. One of the things you’ll note is that if we choose the right pain point or if we choose the wrong pain point, then you’ll start finding solutions. So, you’ll start finding those metaphors that may or may not work. You have to really understand and not proceed on assumption. Kelly’s question could actually invite a lot of different elements to it that as we think about it, could leave you down different roads. This goes back to really understanding before we start to try to solve. And I’ll just kind of double click on that just a little bit more.

Dan Seewald: The double click is that we often just jump right to ideas because ideas are fun. The understanding piece, the listening, the asking questions, the visually mapping a problem allows you to find the right place or the optimal place, maybe not the right place, but the optimal place to start. Once you have that, then you can start to really be expansive and be divergent in all the different ways that you could approach that problem from a metaphorical standpoint.

Framing the Problem

Dan Seewald: So you could, this is, I think a really, just a great kind of example in action – not rehearsed in any way – that really could demonstrate how you could lead down the wrong road or you could also go down the right road if you do the right things and take the right amount of time to be able to explore and understand the problem.

Nora Herting: Right, I agree. I think it’s a great test case because we’re not all doctors or in life sciences, but we’ve all been patients for one thing or another. And it’s a little bit like the design thinking principle we talk about too, which is how are you framing the problem?

Nora Herting: One could be, yeah, the patient doesn’t feel empowered. Another one might be that the HCP is booked so tightly that they don’t allow for questions, right? So, depending on how you understand the problem or frame the problem, it’s going to take your ideas in a different direction. So, thank you, Kelly, for chiming in with that. It’s a great one. And for those of you out there, it might be thinking, let’s put this into practice. What would be some metaphors for Kelly to think about this and truly understanding the problem?

How COVID Has Disrupted Innovation

Nora Herting: So Dan, this has been so much fun and we’re burning through our hour almost, but I want to talk about innovation in terms of where we are right now with the disruption that we’ve had with COVID, with ImageThink like most companies, right? We all started working differently, working virtually. We started changing our service, supporting our clients virtually. How have you seen working with clients, innovation change or the needs or the conversations around innovation while people have now come to work differently?

Nora Herting: I think that this innovation theater that Kelly Evans spoke to, in our mind is all people together in a beautiful space with a whiteboard, which clearly is not happening a whole lot these days. So I’m just really curious if you want to share what has been your thought or your experience with clients around how innovation or the way we think or do innovation might have shifted.

Pre-COVID to Now

Dan Seewald: Yeah, it’s shifted a lot. So, the biggest shift at a kind of a more macro level is if you think about, you’re working from home now, maybe you went to the office on a daily basis, you had a commute, you went into the office, you met with people, you were in meetings physically with people, maybe not everybody, but a lot of people.

Dan Seewald: In that time, you were able to have sort of those respites or those pregnant moments to be able to reflect and meditate. Working from home, many people are now finding they’re going from meeting to meeting to meeting to meeting. They’re booked one after the next. Now, that sounds awesome when you think about productivity. A lot of companies are cheering this on. When you look at some of the organizational level productivity figures that have been produced and shared, what you see is that we’re at all time unprecedented levels of worker productivity. And that sounds great except when you think about creativity and innovation.

Productivity vs. Innovation

Dan Seewald: Productivity is at times the enemy of innovation. Now, a lot of people don’t think about productivity and sort of the economic sort of framing of productivity, but it’s the time worked for an individual person and the time allowed. So, we’ve actually expanded our denominator. But that denominator expansion has come at the time you might’ve been on a train or in the car or walking home or taking a bike ride. It’s eating away at those pauses and moments where we need to actually reflect. It disrupts our inherent flow. And a lot of times that’s where our most creative ideas come from.

Dan Seewald: They happen when you’re in the shower, but maybe taking a jog or just having a casual conversation while getting a cup of coffee with somebody. Those moments have started to bleed away. And because of that, people are more productive, but they have less ingenuity and less innovation. And that’s been one of the most common quips that I’ve heard from senior leaders. We’re getting a lot done, but we’re not doing a whole lot differently. And we need some moments of innovative meaning to be able to do it. You can do it virtually, but you have to be really, really intentional about it.

Changing People’s Habits to Encourage Innovation

Dan Seewald: We spend a lot of time changing people’s habits and tendencies. I did some work in years before in behavioral science and behavioral econ, and a lot of it is around design, making the right choices and designing for people’s experience. And virtually you have to do even more design than ever before than when you were in person, but it can be done. But you have to be intentional about it. You have to want to do it, and you have to value innovative output, speculative efforts versus sheer quantifiable productivity.

Dan Seewald: And that’s a tough thing to trade off on. People love productivity numbers. You look great, except when you need to do things differently. And that’s when the house of cards comes down. So that’s probably been one of the most common themes that I’ve seen, and it’s kind of coming home to roost now. And you’ll see a lot of leaders, a lot of people who need to do things differently are asking, “What can you do to help me?” And we get lots and lots of calls and inquiries about that exact question about how to train and enable people and actually show it for people. So, I would say that’s probably one of the top things that I see.

Sustaining Innovation

Nora Herting: Right, so you’re saying that people are becoming aware of the difference between productivity and innovation. Maybe it’s actually a great moment for innovation in itself that people realize that it’s separate and it takes a different type of approach, right? It’s not the – everybody go along with what you’re doing, the experts are experts and there’ll always be experts. So, to that, and I’m curious if other people are seeing, how has innovation in their own companies shifted with COVID?

Nora Herting: I know that for us, we talked a little bit about fear being a short-term driver, but that certainly, the disruption that we felt and we had an image think spurned a lot of things that were very different. We innovated a lot. And some of you who are joining us might be in that boat too, where there was, out of necessity, a lot of innovation really quickly. But do you all out there have questions for, what does that look like now? Or how is that impacted? How is innovation changed? Because the question that I have, Dan, is when you have a company or you’re in a situation where there has been innovation or these changes, how do you sustain that momentum, right?

Nora Herting: Do you see that certain companies are just very good at not one pivot, but continually fostering that? Because as we talked about, to Kelly’s question is, it takes a lot of work to make it happen. It takes a lot of execution. So, what would you advise around sustainable innovation or keeping that change and that mindset going?

Looking At the DNA of Your Leaders and Organization

Dan Seewald: Yeah, I mean, the old cliche, the, or kind of aphorism that if you want to give, if you want someone to eat for a day, give a person a fish. If you want them to eat for a lifetime, teach them how to fish. It’s very much the same thing here, that people run workshop sessions, they’ll bring in third parties, and we’re happy to help on the kind of the one-offs. But if you really want to make innovation sustainable, you have to get into the DNA of the organization and of your people. And that means understanding what is the mindset, climate and culture, and what are you going to do if you don’t feel like it’s up to snuff, which often it’s not.

Dan Seewald: And then how do you enable people train them? How do you kind of address some of the underlying cracks in the wall to be able to enable innovation to thrive? One of the most basic things that a lot of companies don’t have is the, this notion of psychological safety. That term gets thrown around a lot. A lot of people don’t necessarily fully appreciate what it means.

Encourage People to Pivot, Fail, and Innovate

Dan Seewald: And it’s this idea that people are not just comfortable putting themselves out there, but they don’t fear retaliation, that there is an environment led by your leaders, role modeled by them, that invites people to pivot, to fail, to do things differently. And it’s not just a couple of people, but it’s across the hierarchy of the organization. Things like that enable for sustainable innovation. And it takes leadership, and it takes purpose. So, there are a lot of things that have to happen. They can be trained, they can be taught, they have to be hired in for as well.

Dan Seewald: So, it starts at the kind of the building blocks and the DNA of the organization. So, when people think about innovation and a lot of people don’t differentiate between the organizational side, it’s kind of like, oh yeah, we can do that. And that’s all feel good. That’s hard to measure and quantify, for the long run. That’s the fishing that you’re teaching. The shorter run are these projects, initiatives, partnerships, collaborations. And those are important.

Dan Seewald: Those might be the proof points or the evidence that you build, and you give to your scene leaders is say, “If we really build our culture and a climate of this, we could do this more sustainably.” But it takes time and investment, and you have to have leadership buy-in and role modeling of that to make it stick. So, it just doesn’t happen overnight. And it does take time, but that’s kind of how I think about how you build sustainable innovation is that it starts throughout the DNA of your company and your leaders.

Implementing Innovation into Your Culture

Nora Herting: Yeah, that’s probably very true, going back to just having that buy-in. So, thinking again, also about the question that Peter asked earlier, when you’re in a culture where you have this expert mindset, this fixed mindset, and how do you start? What would you say would be helpful for everybody out there listening, thinking about the innovations in their own companies and maybe acknowledging it’s a little bit harder to do right now, we’re prioritizing productivity, as you said, over innovation.

Nora Herting: What would be, what is what effective cultural value or behavior that you’ve seen that we could think about trying to implement in our organizations?

Dan Seewald: Yeah, I mean, there’s, so two things I’ll mention. One is around this idea of nurturing or building on each other’s ideas. It’s so basic and fundamental, and we just don’t do it, or not enough. Some people are good at it, but I would actually get people, when someone comes to you with an idea, to build in the practice and the habit of listening, not critiquing or judging right away. Our initial instinct is to kill ideas. We are kind of natural born idea killers. So actually, working on that habit of nurturing building ideas and finding possibility,

Dan Seewald: That in and of itself is a kind of a unit level or individual level skill that leaders can do, what individuals can do, and it’s a practice and a habit, which even when you’re the most seasoned innovator that you can forget about, you can absolutely forget about it. So something like that is a great thing to work on.

Start Small

Dan Seewald: And how do you do it? Small bets, little, small things. It doesn’t have to be on the most grandiose projects. Make it small, do it for an hour, do it on one meeting, do it in one session. Doesn’t have to be, I’m going to do this for the next month. That’s a little bit overwhelming. If you want to create change, you have to do things in small ways. We’ve learned that from behavioral science, that small steps, little bets, or what win the bigger picture and the bigger game.

Dan Seewald: So, create little computations. I’m going to try to nurture or build on someone’s idea. And you don’t have to be overboard with the theatrical of, oh yes, and everything. Like, you know, people will start to be bothered by it if it’s a little too much, a little too overboard.

Dan Seewald: Do it in little subtle ways. And that’s a little thing that anybody here can do. And I could tell you, I did a written article, if anyone’s interested, it’s a little bit tongue in cheek, but it was real. It was called “24 Hours of Yes”, where I challenged myself to say yes and build on every single thing that I heard. And my kids kind of caught onto that after about maybe 12 hours and started saying, can I go out all night and go out with friends and party? Can I go do this? And so I had to try to kind of rejigger my position a little bit, but, you know, it actually was incredibly liberating and incredibly hard to always find the positive and nurture ideas. So I’d give you that, try that out, little small things that you can do.

Where to Find Dan Seewald

Nora Herting: So small bets saying yes, listening to people’s ideas, starting small, I love that actually. And hopefully that resonates with Barbara Braun, who just asked, you know, how do you build this in to the DNA when you’re in a company that’s constantly changing roles?

Nora Herting: So that’s fantastic, because that’s like you said, the individual contributor, something for us all to remember, that will help build that culture of safety and risk-taking, right, that you’re talking about as being a bigger cultural element. I want to make sure that we have time to hear about what you’re doing next, Dan.

Nora Herting: Dan does have his own methodology at the deliberate innovator built, I think, on probably the best of lots of different practices. And he’s so generous. There’s many great videos out there, including the one that talks about this metaphors innovation. And you get to hear a little bit more about the ban and the deodorant story. But Dan, what are you excited about next? And if folks wanna hear more, connect with you, where do they find you?

Dan Seewald: Yeah, I mean, you can email me, dan at deliberateinnovation.net. You can call me, you can find my stuff online, on my website as well. And, you know, it could be to chat. You could also hit me up on LinkedIn. You know, we’re all tethered to our technology these days. So you can find me if you wanna chat. If you just have a thought or you disagree with something, or you feel like we didn’t go deep enough, because we could go a lot deeper on every one of these topics, happy to.

Dan Seewald’s TEDx Talk on Neurodegenerative Diseases

Dan Seewald: You know, it’s something that I’m very passionate about. And kind of the next big things, you know, did a TEDx Talk with NGIT a little while ago. They’re trying to bring it to the main stage, which would be great. It’s about a topic that I feel very strongly about, which is about neurodegenerative diseases and what’s stopping us from bringing the solutions.

Dan Seewald: Like we saw with Project Warp Speed, why can’t we and why haven’t we be able to gather together to solve some of these neurodegenerative diseases, like my father and my grandfather had Parkinson’s disease, or Alzheimer’s, Huntington’s disease. We have the capability and the wherewithal. And actually it’s a great example of metaphors of where else could other people apply things they’re doing. In the citizen science community, everyday scientists or non-scientists, people like all you and me that can contribute to moving the needle, which I’m 100% sure that we can, because there’s a lot of precedent for it.

Dan Seewald: So, I’m not just an advocate. It’s not just a great story, but it’s something personally that I feel strongly about. I’d love to see that change. So, you know, every project and thing that you work on, you’re hoping it’s going to make a difference. It’s not just about turning a buck; it’s about actually making a dent. You know, one great mindset, you want to make your dent in the universe. And, you know, I’d like to make mine about changing people’s minds around how do you solve problems? I see it every day and I’m looking forward to seeing some greater impact in the things that matter most to me.

Closing

Nora Herting: That’s great, Dan. It’s been such a privilege to have you here. And I’m sure that every cause that you’re putting your intention behind from Parkinson’s to all the myriad client problems that you’re working on are going to benefit from clear thinking and insight around how you frame up a problem, how you understand the problem, how you approach the problem.

Nora Herting: So I agree, we could have went deep into all of these. It was so much fun. We didn’t even get to nerd out about Fleming and Penicillin. So that’ll be another time. But I think we could have worked it in here. So, thank you so much. If you would like to circle back to hear this again, you can find it at imagethink.com backslash event.

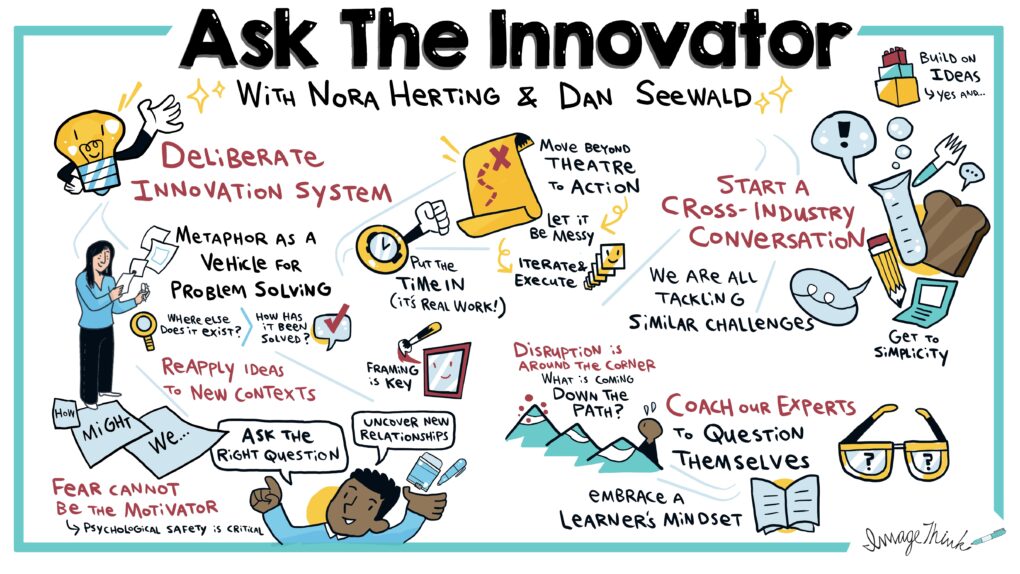

ImageThink’s Graphic Recording of the Conversation

Nora Herting: Also very visible, very silent member. This production today was Aaron Maper who has captured, I think so beautifully some of these great concepts that Dan has introduced. So, this will also be living on LinkedIn. So, you can access the visual summary, Aaron from ImageThink created. Thank you, Aaron for that. And thanks again, Dan, for joining us.

Nora Herting: We’ll reach out to everybody who posted comments, questions and choose a winner to receive, Draw Your Big Idea and join us back next month in May where I will have another guest expert on. I’m very excited about it.

Final Thoughts on Innovation

Nora Herting: Dan, any parting thoughts before you go for us to remember when we think about innovating?

Dan Seewald: Only parting thought is enjoy the fresh air and the beautiful outside while you can and I look forward to chatting with everyone at some point in the future. So be well and stay innovating.

Nora Herting: Great, thanks so much, Dan.